Home

Home Up

Up Search

Search Mail

Mail

NEW

Measurements on Dutch passage mounds

(One of?) the first web pages on Dutch megalithic passage mounds

(since

beginning 1996)

An e-group

has been set-up to look into these Dutch monuments. It is at this

moment looking into the protection around the oldest monuments in The

Netherlands.

Orientation measurements

Orientation measurements were done on almost all of the Dutch passage

mounds.

From an overview and discussion on these results

one can see that most chamber of the Dutch passage mounds are oriented

along east and west.

Below a pictures is given of the number of passage mounds that have

a particular orientation (a comparable investigation has been done by Bom,

F. and see also Orientations

of the Dutch Hunebedden).

From this picture one can deduct that most chambers are oriented

between

246o and 305o (75% of measured passage mounds).

The

main declination will be between: -14o and 20o.

The

declination

is not really dependent on the altitude of the horizon, because in this

region of The Netherlands the horizon could be at maximum some 10 [m]

lower

than at the location of the passage mound (or the effect of trees had

to

be significant in the past).

Comparable orientations can be found on the German

passage mounds (of the same time frame, 3300 BCE to 2600 BCE, close

together [100 km], and comparable cultural environment [Funnel Beaker

Culture]).

Possible explanation for this distribution

The orientation of the Dutch passage mounds is around 270° +/-

25°

(or of course 90° +/- 25°).

I have the following theory that the deviation has to do with the

full

moon positions around equinox at building time of the mounds:

- The deviation of the Dutch passage mounds is around 270° or

90°,

so a relation with equinox (my definition of equinox is that sun sets

or

rises at 270° or 90°: around March 18th, 1999 AD)

could

have some significance

- The main reason why I think that it is not equinox that former

people

were

interested in, is because it is not a very interesting day in many

cultures.

Perhaps a full moon setting before or after equinox is much more

appropriate

for a rite!

- Furthermore and more important: I don't think it is equinox

itself,

because

there are clusters of mounds standing very close to each other (up to

three

within 50 m), which still vary in the orientation of the main axis by a

few degrees.

- Related to something like easter (Christian calendar)?

Easter Sunday is to be the first Sunday after the first full moon

after the 21th of March (spring equinox). If this full moon falls on a

Sunday, it is to be the following Sunday.

For calculations of Easter sunday; see here.

But I have the idea that the megalithic people also looked after

autumn equinox (or before spring equinox), because the

distribution

is not one sided around 270° or 90°. - Related to Harvest

Moon (full

moon closest to autumn equinox)?

- The altitude of the horizon could be of influence, but the height

differences

in the Netherlands are not very large (in Niedersachen,

where 53 mounds were measured, the horizon has more height

differences).

It could be that the height of the trees in the surroundings is

important...

Difficult to determine.

- The max. difference between sunset (or sunrise) azimuths some 29

days

(the

moon's orbit time) before and after equinox is around 2 * 17°.

If you include the max. moon set/rise difference due to its

inclination/perturbation,

the moon's azimuth before and after equinox can vary around 2 * 17°

+ 2 * 9° (at a latitude 53°) = 52°. In the below picture

the

moon's azimuth is determined from its actual (ephemeris) moon sets in

the

time period 29 days before/after equinox.

This 52° is thus comparable to the 2*25° measured orientation

of the passage mounds! - The question is, if we calculate the full

moon set (or rise)

azimuths around

equinox, do we get a comparable distribution of orientations as

actually

measured with the passage mounds?

Here is the distribution of calculated full moon setting between

1999-2092

AD (5 times the nodal cycle) before and after spring

equinox

(calculated with the help of the JPL's

HORIZONS ephemeris) and the distribution of the orientation of the

passage mounds in The Netherlands and Germany:

- The interval width of this distribution is 10°, because

according

to

normal statistical practice an interval should hold at least 5 to 10

sample

. Because the number of passage mounds in the Netherlands is 54, and

the

distribution spans some 60° (from 250° - 310°), the

interval

width should be at least 6°. So the chosen interval of 10°

seems

to be oke.

This interval value will thus obscure any perturbation/etc. effects

of the moon's orbit and also most inaccuracies of the measured

orientation

(1 sigma around 1°).

- The distributions look comparable, but if using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov

test (Dn*) it looks as if the orientations of the NL and DE passage

mounds don't have the same distribution as the azimuths of the full

moon

setting around equinox.

- When using the Chi-Square test (5 intervals [4 degrees of

freedom] to

keep

the number of samples per interval > 5) for both the NL and the DE

passage

mounds the hypothesis (that the distribution of azimuths of the passage

mounds is equal to the full moons azimuths around equinox) is rejected

(99%).

Other possible explanations

- Other locations where

similar

alignments

are found at Armenoi, Crete

- Dig mound by eye (Keith Pickering)

How about:

- Ancient cultural requirement to orient mound passage E-W for

religious

reasons;

- But (unlike our own culture) little cultural interest in

actually

measuring

things.

- So you dig the mound with an east-west orientation, as

determined

roughly

by eye.

About 25 degrees of scatter seems about right.

Remark VR: Could be indeed. - The orientation could be

towards any planet, because any

planet/moon on

the ecliptic gives the same orientation variation as shown above.

Remark VR: Not true, there is still this +/-25° distribution.

So equinox itself was important. Furthermore I think the moon is more

important

in most cultures then e.g. Venus or Jupiter. And full moon is a very

distinct

feature in the sky, which has been an important factor in a lot of

cultures.

Spliced stones

Like mentioned by several people (Bom, F.

and

Bakker,

J.A.), some stones seems to be spliced. Some good examples are cover

stones 1 with 2 and 3 with 4 of D25 and cover

stones 1 with 2 of D29.

Spliced stones at D25

Here are two examples of the splitting:

- cover stones 1 and 2

A lot of points on cover stones 1 and 2 provide evidence of the

splitting.

One of these evidences can be seen in the below pictures.

The scale and angle of the two pictures is different! Furthermore:

the brownish is the flat face of the stone while the greenish part is

the

vertical step.

A step in the underside of cover stone 1

A step in the underside of cover stone 2

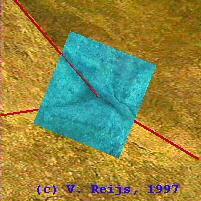

- cover stones 3 and 4

First we see two pictures of a three sided pyramid on the undersides

of cover stone 3 and 4. On stone 3 the pyramid comes out of the stone

and

at cover stone 4 is thus goes inward.

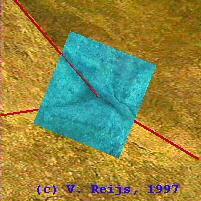

Outward 3 sided pyramid on cover stone 3

Inward 3 sided pyramid on cover stone 4

In the following picture one sees the superposition of the two

pictures:

Superposition of pyramid 3 (brownish) with pyramid 4 (bluish)

Spliced stones at D29

The geometry of the undersides of cover stones 1 (blue) and 2 (red)

(error

in length around 2%):

More specific geometry info:

| side |

stone 1 |

stone 2 |

| # |

[mm] |

[mm] |

| 1 |

1200 |

1100 |

| 2 |

1700 |

1750 |

| 3 |

1000 |

1140 |

| 4 |

2000 |

1800 |

| 5 |

700 |

860 |

| 6 |

1660 |

1700 |

|

==== |

==== |

| Total |

8260 |

8350 |

Possible methods to split stones

There are some ideas how people could have spliced megalithic stones

(of

granite, gneiss, etc.):

- just by coincidence (perhaps because of frost/water/etc.). An

example

has

been seen in Ireland, Co. Wicklow.

- people pushed them over a hill lock. There are not many of them

in The

Netherlands;-), so this I would rule this out.

- They used fire. An even split could be made by put a burnable

string of

some material (palm e.g.) around the rock, burn this material and then

pour water over it. The stone could split just a the 'circle' where the

material was.

- they used wooden pegs to split the stone (like we still do with

iron

pegs).

Would that be feasible on gneiss and granite?

- usage of wooden poles in round holes. By making the poles wet,

the

stone

splits (practice in Greece and Italy).

- use little interstices, filling them with water, and allowing

them to

crack

due to frost (with the aid of wooden poles and so on).

- by laser, but I don't think the people at that time will have had

this

and the surface is not regular enough to support this.

- using cleavage, which is a predictable way splitting

occurs. At

least it was predictable to the ancient masons. It may be relevant to

recall

the Danish scientist Steno who, in the 1600's announced the 'law of

constancy

of interfacial angles', which observed that no matter how large or

small,

narrow or thick, the angles of quartz prism faces remained constant...

always 60 degrees.

- The slight variations observed on sites just 50m away from one

another

indicates a "processional " and that the event was "probably" tracked

on

foot between sites by the people who built them (Dutch Neolithic Beaker

culture) so that the entire sunrise and possibly sunset and (as

here

suggested) full moon or even eclipse track could be observed, prayed

to,

offered to, worshipped etc. The sequence would depend upon which end

allows

the aperture (opening).

- your idea! Please send them to me!

Links to other sites

Disclaimer and Copyright

Home

Home Up

Up Search

Search Mail

Mail

Last content related changes: Aug. 24, 2000